Here, we invite you to embark on a journey of self-discovery and discernment as you explore the calling to monastic life.

Here, we invite you to embark on a journey of self-discovery and discernment as you explore the calling to monastic life.

Pax

What is a Monastic Vocation?

A monastic vocation is a unique calling to live a life of prayer, community, and service within a monastery. It is a commitment to seek God through a disciplined and contemplative way of life, following the Rule of St. Benedict or another monastic tradition.

What is a monk?

One image that the word ‘monk’ brings to mind is that of the monastery. This is nothing more than a family of monks, living under a superior and spiritual father, all of whom seek to be alone with God, and all of whom do so, strange to say, in common – praying, working, eating, even playing together. It is this that one learns to prefect the virtues of obedience and charity, which one might not be able to practice fully if he is strengthened in his purpose, profiting by the example of his fellows, and sharing his own strength and peace with them.

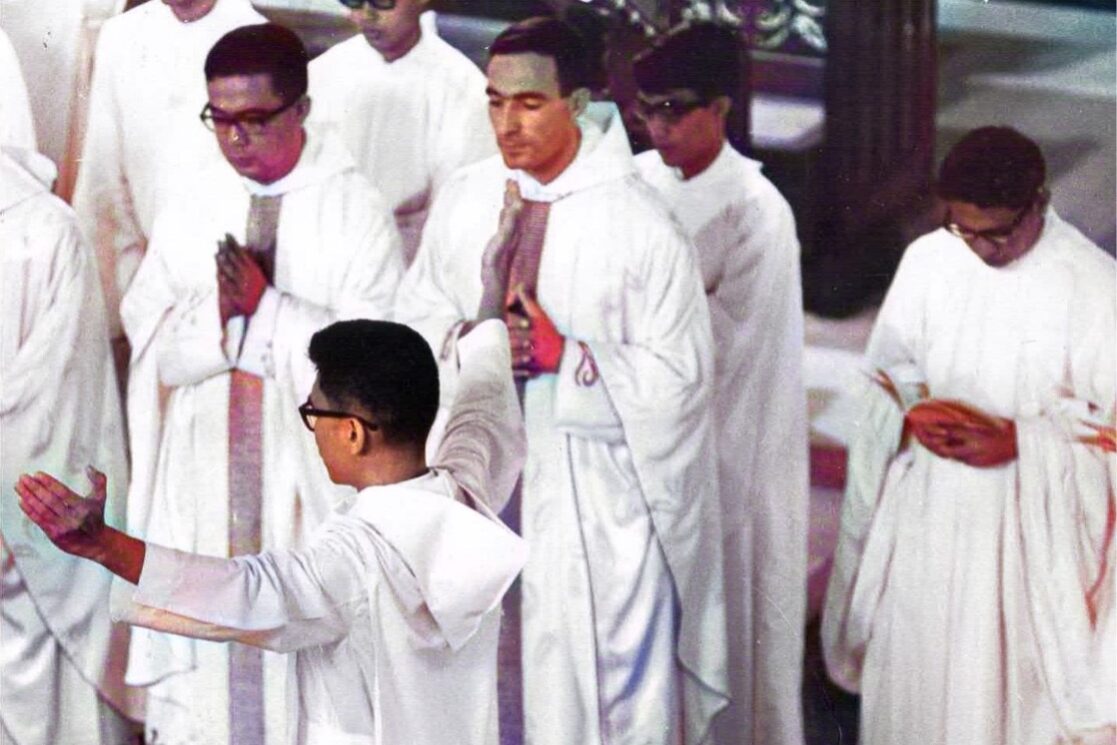

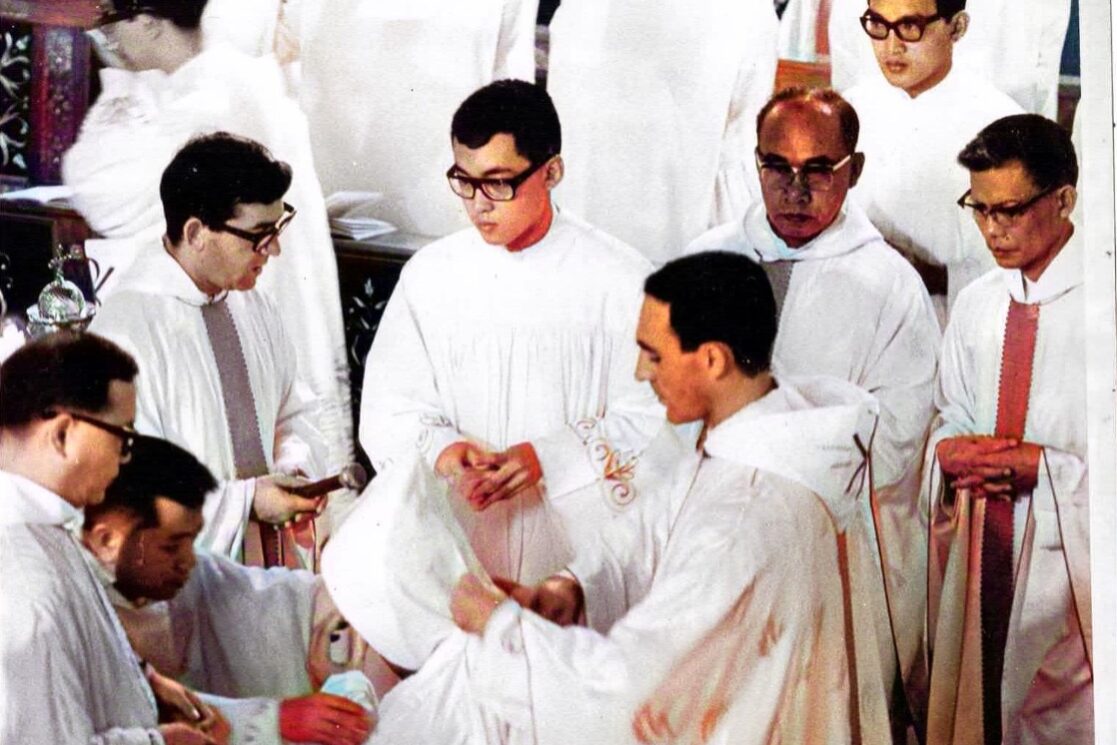

Not all priests are monks, and not all monks are priests – some people are inclined to confuse both terms. Of course, there are monks who are also priests, and there are monks who are not priests. The latter are known as professed monks (with religious vows). Priests are ordained minsters of God with certain powers and faculties, such as offering the Holy Sacrifice of Mass, forgiving sins, and administering other sacraments. Monks are religious bound by vows, living according to a rule in a community under a superior. One may say that although both priest and monk serve God and strive for Christian perfection, what makes a priest is the sacred office, but what makes a monk is the total sacrifice of self.

A monk, in the fewest possible words, is a man alone with God. That is what a monk strives to be in this world. A more precise definition of a monk would be: one who is bound for life by religious vows, and lives, according to rule, under a superior and in seclusion, in a permanent community which observes a life of common prayer, and which has no other specific fundamental aim than striving for Christian perfection. The vital aspects of monastic life are implied here: the monk forsakes the world and seeks God.

Monastic spirituality in the early centuries

The monastic idea has a history that goes farther back than Christianity itself, back to the ascetics, hermits, and virgins of old who pursued some spiritual ideal through renunciation and good works. Christian monasticism, however, did not merely evolve from that. It was in fact established by Jesus Christ as the best way of living a Christian life when he said, “If anyone wishes to come after Me, let him deny himself, take up his cross, and follow Me.”

In the early centuries of Christianity, a great number of men pursued that ideal, but one man in particular had a way of pursuing it which is widely followed even to this day. That man was St. Benedict, 480-547 A.D., who followed several monasteries in Italy and wrote the Holy Rule, a document celebrated for its prudence, discretion and adaptability – the rock on which Benedictine monasteries throughout the world are founded.

The Rule: Unique to the Benedictines

The Holy Rule is what makes Benedictine monks different form other religious who are also bound by vows and are obliged to strive for Christian perfection. Whereas later religious orders and congregations were founded with a specific purpose in society – for instance, missionary work, combatting of heresies, preaching, education, scholarship, care of the unfortunate – St. Benedict wrote his rule with no other purpose in mind but the sanctification of man and the glorification of God through work and prayer. St. Benedict laid down very precise instructions for the common prayer of his monks, but he did not specify any particular line of work for them, although he stated in general the necessity and value of study and manual work.

The adaptability of the rule has enabled Benedictine monks throughout history to answer the needs of their time, their country and their people. They have won souls for God and have contributed to the rise of civilization by working as missionaries, pastors, teachers, scholars, artists, craftsmen, and farmers. The conversion of England, Germany, and Scandinavia to Christianity, the establishment of a system of education in the Carlovingian empire, the preservation of the ancient classics through the copying of manuscripts, reforms in the Church, the improvement of farming methods – these are but few of the valuable contributions of Benedictine monks during the early years of Christian civilization.

The Benedictines: Then and now

The first Benedictines who came to the Philippines in 1895 worked as missionaries in Surigao, then established a school, San Beda College, in Manila in 1901. At present, the Benedictine community in Manila, more properly called the Abbey of Our Lady of Montserrat, plays an important part in the liturgical renewal in the Philippines and continues its educational mission through San Beda University.

Alone with God

But is all this activity not incongruous with that idea of ‘a man alone with God?’ To be alone with God does not necessarily mean that one should be a hermit. The Benedictine monk is in the world, but is not of the world. Whatever he does for society is motivated by the love of God. In obedience to the teachings of Christ, he sees God and serves God in mankind, and what he does is not for his personal gain but for God’s glory.

His aloneness with God and his detachment from the world are realized through observance of the vows of obedience, conversion of life (which embraces poverty and chastity) and stability. By vow of obedience, he renounces his will and submits himself wholly to his superior; by the vow of conversion, he puts himself under the obligation to strive for perfection, renouncing all sin, as well as the right to private property and marriage; by the vow of stability, he attaches himself for life to one particular monastery. By all these he renounces not only attachment to the world, but also love of self. He lives no longer for himself, but entirely and exclusively for God.